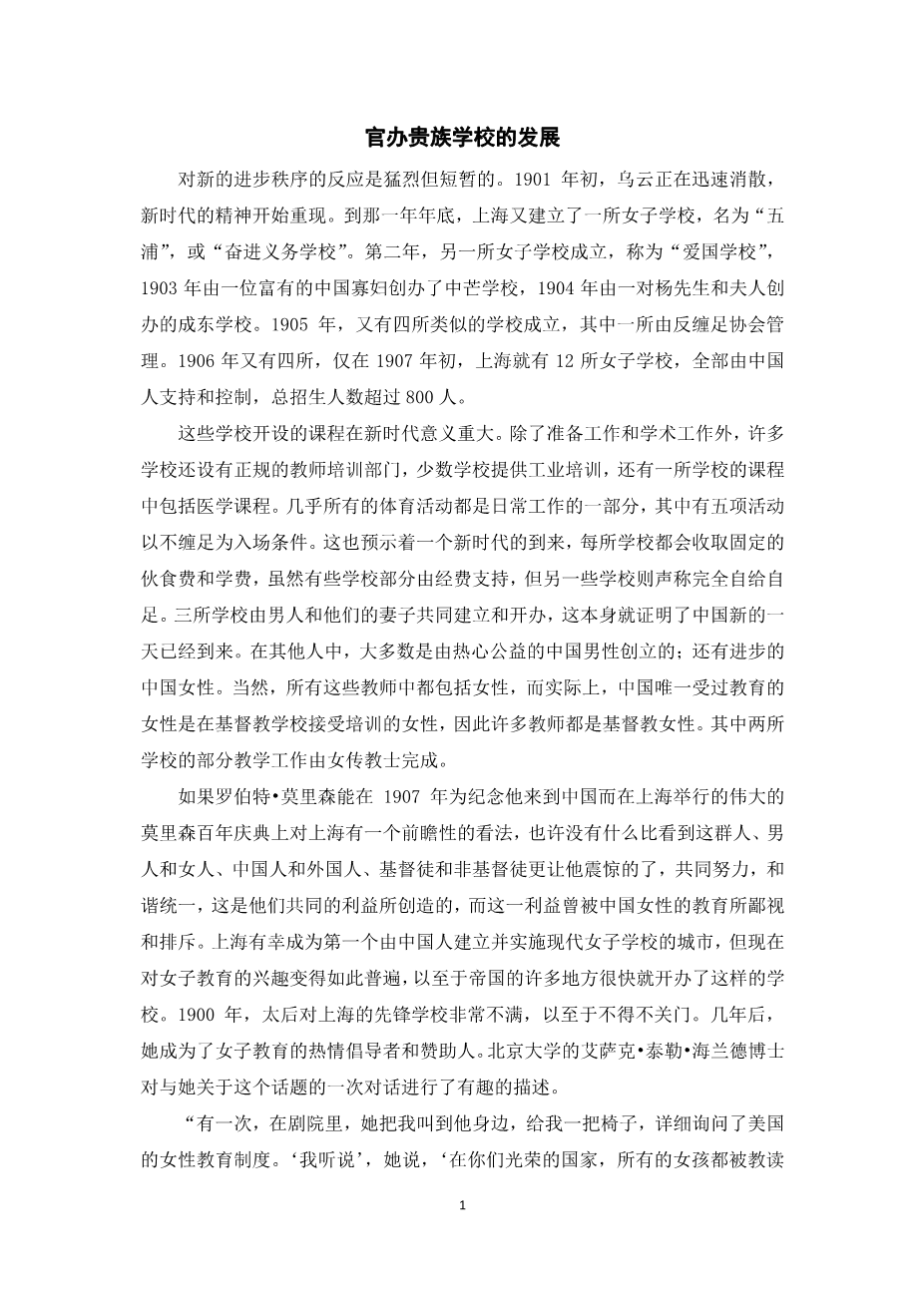

官办贵族学校的发展外文翻译资料

2023-05-04 19:27:06

附录一 外文原文

THE DEVELOPMENT OF GENTRYAND GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS

THE storm of reaction against the new order of progress was severe, but short. At the beginning of I901 the clouds were rapidly disappearing and the spirit of the new era had begun to reassert itself. By the close of that year another school for girls had been established in Shanghai, bearing the name “Wu pun,” or Strive For Duty School.' The following year another school for girls, known as the “I-Kwo,” or “Patriotic School,” was established, followed in I903 by the Chung-mang School, founded by a wealthy Chinese widow, and in I904 by the Chrsquo; Eng Tung School, established by a Mr. and Mrs. Yang. The year 1905 marked the founding of four more similar schools, one of them under the management of the Anti-Foot-binding Society. Four others followed in 1906, making at the beginning of 1907 a total of twelve schools for girls in Shanghai alone, supported and controlled wholly by the Chinese, and with a total enrollment of over eight hundred students.

Very significant of the new era were the courses of study offered in these schools. In addition to the preparatory and academic work, many of them had normal departments for the training of teachers, a few gave industrial training, and one included a medical course in its curriculum.

In almost all, physical culture was a part of the regular work, and in five of them unbound feet were made a condition of entrance. It was indicative of a new era, too, that in each school regular rates of board and tuition were charged, and that whereas some were partly supported by subscriptions others claimed to be wholly self-supporting. Three schools were established and carried on by men and their wives, working jointly, this in itself a proof that a new day had dawned in China. Of the others, the majority were founded by public –spirited Chinese men; there remainder by progressive Chinese women. All, of course, included women on the staff, and as practically the only educated women in China were those trained in Christian schools, it followed that many of the teachers were Christian women. In two of the schools part of the teaching was done by women missionaries.

If Robert Morrison could have had a prophetic vision of Shanghai at the time of the great Morrison Centennial held there in 1907 to commemorate his arrival in China, probably nothing would have caused him greater astonishment than the sight of this company of people, men and women, Chinese and foreign, Christian and non-Christian, working together in harmonious unity created by their common interest in that once despised and rejected cause -the education of Chinese women.

To Shanghai belongs the honour of having been the first city in which a modern school for girls was established, and carried on by the Chinese, but interest in womans education had now become so general that such schools were soon started in many parts of the Empire.

The Empress Dowager, who in 1900 had so frowned upon the pioneer school in Shanghai that it had been forced to close its doors, be-came, a few years later, a warm advocate and patron of womans education. Dr. Isaac Taylor Headland of Peking University gives an interesting account of a conversation with her on the subject.

“lsquo;On one occasion while in the theatre she called me to he side , and give me a chair, inquired at length into the system of female education in America.rsquo;

“lsquo;I have heard,rsquo; she said, lsquo;that in your honourable country all the girls are taught to read.rsquo;

“lsquo;Quite so, your Majesty.rsquo;

“lsquo;And are they taught the same branches of study as the boys?rsquo;

“lsquo;In the public schools they are.rsquo;

“lsquo;I wish very much that the girls in China might also be taught, but the people have great difficulty in educating their boys.rsquo;

“I then explained in a few words our public school system, to which she replied:

“lsquo;The taxes in China are so heavy at present that it would be impossible to add another expense such as this would be.rsquo;

“It was not long thereafter, however, before an edict was issued commending female education, and at the present time hundreds of girlsrsquo; schools have been established by private persons both in Peking and throughout the Empire.”[1]

At the orders of the Empress a large Lama convent was transformed into a school for girls and it is reported also that she gave 100,000 tales (about $65.000) to the cause of womanrsquo;s education in Peking. Other women of wealth and rank were quick to follow her example, and girlsrsquo; schools sprang up in many parts of the Empire.

Mrs. Isaac Taylor Headland, who through her skill as a physician had become acquainted with many of the women of this class, tells of a visit to the school conducted by Princess Su in a building within her own palace grounds:

“The school building was evidently designed for that purpose, being light and airy with the whole southern exposure made into windows and covered with a thin white paper which gives a soft, restful light and shuts out the glare of the sun. The floor is covered with a heavy rope matting, while the walls are hung with botanical, zoological and other charts. Besides the usual furniture for a well- equipped school room it was heated with a foreign stove, had glass cases for their embroidery and drawing materials, and a good American organ to direct them in singing, dancing and calisthenics.

“I arrived at recess. The Princess took me into the teacherrsquo;s den, which was cut off from the main room by a beautifully carved screen.

Here I was introduced to the Japanese lady teacher and served with tea. She spoke no English and but little Chinese and the embarrassment of our effort to converse was only relieved by the ringing of the bell for school. The pupils, consisti

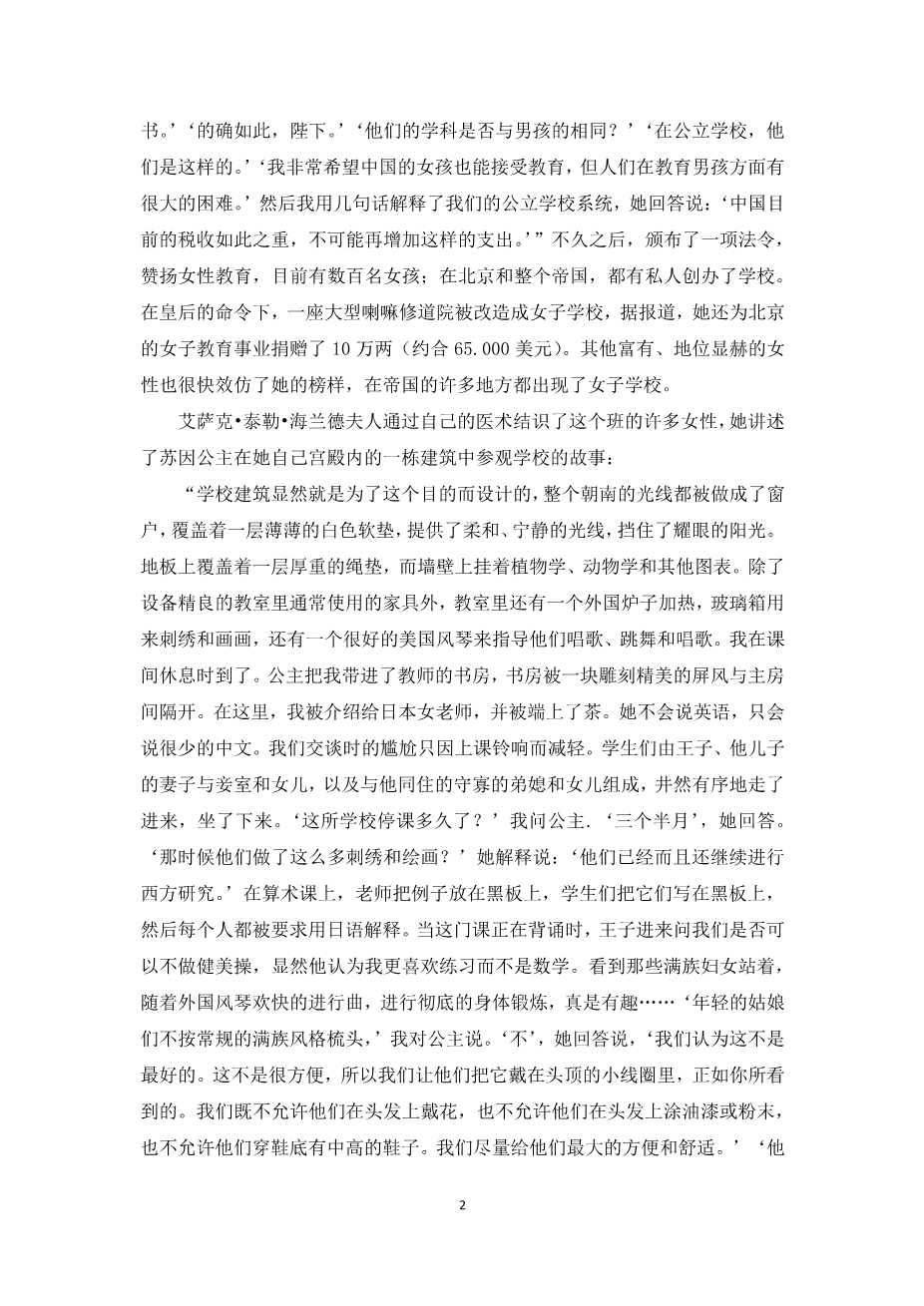

剩余内容已隐藏,支付完成后下载完整资料

英语译文共 6 页,剩余内容已隐藏,支付完成后下载完整资料

资料编号:[591773],资料为PDF文档或Word文档,PDF文档可免费转换为Word